The Logics of Concession: Protest Economies and Public Authority in the Maghreb

Book project in progress

Where party systems and welfare institutions are weak or co-opted, protests become an important means by which citizens make distributive claims on the state. Particularly in underserved regions and neighborhoods, citizens often encounter the state — in both its deliberative and repressive functions — through participation in demonstrations, sit-ins, and strikes. Iterative rounds of mobilization and state response become an arena where claims to social citizenship are adjudicated and policies aimed at redressing (or suppressing) social grievance may be forged.

This project asks: what factors shape state response to protests demanding economic opportunity and social provision? How do revolutions and regime transitions — often construed by citizens and scholars as opportunities for redistribution — transform the ability of social protest movements to gain concessions in line with their demands?

I argue that political regimes shape the fundamental logics by which elites and authorities respond to social protests. In an autocratic system, elite responses tend to reflect a logic of threat containment. Grievance (the popular impetus to mobilize) and threat (the elite expectation of escalation and displacement associated with particular forms of mobilization) are mutually constituted through historical experience. When protests become sustained, widespread, or threatening to strategic industries, elites in an authoritarian system are driven by an overriding impetus to demobilize, and responses may oscillate between negotiation, concession, and violence until authorities find ``what works.’’ In this context, revolutionary threats — such as Morocco's experience during the 2011 Arab Uprisings — can trigger periods of significant distributive concessions, as authorities seek to divide social claimants from the political opposition. Longer time horizons and extreme centralization can, when necessary, facilitate significant investment. Crucially, authorities often target redistribution to broader social groups tangential to protesting populations, while punishing actual activist leaders through violence and incarceration.

In new democracies, by contrast, I observe that elites no longer uniformly aim to demobilize protest movements in service of regime longevity. Instead, a logic of short-term competition and credit-claiming prevails. Political imperatives may prompt elites to undermine opponents' attempts at social negotiation, to renege on commitments advanced by prior administrations, and to channel exclusive concessions to well-institutionalized groups, often at the expense of neediest claimants. Further, legacies of authoritarian governance and centralization can curtail the distributive and bureaucratic resources available to subnational authorities facing social protest, who often face a lapse in coordination with national authorities. Ad hoc and small-scale concessions to disruptive actors (i.e. ``micro-negotiation’’) are common; enduring social interventions are few.

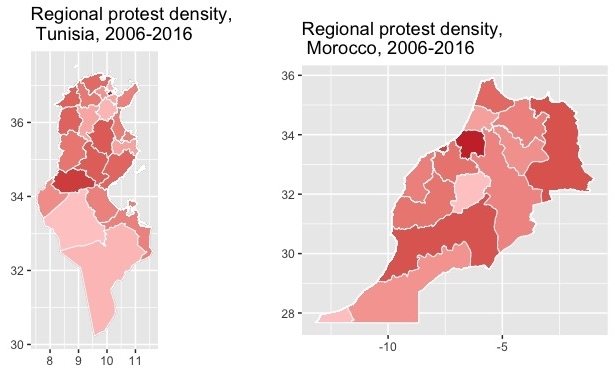

I illustrate these arguments through comparative case studies of mobilization and state response surrounding the Tunisian and Moroccan phosphate mining industries, using interviews with activists and policymakers collected during ~15 months of fieldwork in mining towns and capital cities. I examine quantitative implications using original protest event catalogs sourced from Arabic-language newspapers.

Through close study of vital movements in North Africa, this project contributes novel theoretical perspective towards a global question: why contemporary transitions to democracy may fall short of redressing citizens’ demands for economic opportunity and social protection.

Funding sources: National Science Foundation, Social Science Research Council, American Institute for Maghreb Studies

Awards: Gabriel L. Almond Award for Best Dissertation in Comparative Politics (2021), APSA MENA Politics Section Award for Best Dissertation in Middle East Politics, Honorable Mention (2020), ISA International Political Sociology Award for Best Graduate Paper (2019)

Main road awaiting repairs in Moulares, Tunisia. Photo by the author, December 2016.

Event catalogs show regional variation in protest activity, 2006 - 2016.

Park under construction in Khouribga, Morocco. Photo by the author, March 2017.